What is Coronary Artery Disease?

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a type of chronic heart disease (CHD) or ischemic heart disease (IHD). It develops when atherosclerotic plaque causes coronary artery obstruction, limiting the flow of oxygen rich blood to the heart. This blockage reduces blood flow, resulting in chronic coronary syndrome (CCS) which can trigger heart attacks and cause lasting damage to the heart muscle¹. Coronary artery disease may progress gradually over time without noticeable symptoms. This form is commonly known as “silent CAD”².

However, it can also cause noticeable issues like stable angina and acute coronary syndromes (ACS). ACS includes unstable angina and heart attacks (myocardial infarction). Since CAD is the leading cause of death in CHD, we will call these related conditions “CAD”.

Healthcare providers record coronary artery disease most often under ICD-10 code I25.1, which refers to “atherosclerotic heart disease of native coronary artery”. Variations of this code are employed to indicate the occurrence of angina, a previous heart attack, or long-term ischemic heart disease ³.

CAD in Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Individuals

A common symptom of coronary artery disease is chest pain or discomfort, especially during physical activity. Other signs may include dyspnea (shortness of breath), dizziness or nausea. However, these symptoms do not always mean there is heart disease.

This makes diagnosis hard, especially for patients without a family history of heart problems. In many cases, CAD develops silently, with no symptoms until a sudden cardiovascular event occurs. Studies also show that 50% of men and 64% of women who suffer a fatal heart attack had no prior warning symptoms, averaging approximately 57% across genders⁷. An important fact is that nearly 45% of sudden cardiac deaths (SCDs) happen in people with no history of heart disease¹⁷.

Researchers estimate that between one-fifth and more than half of all heart attacks occur without noticeable symptoms² and an estimated 30% of individuals who experience sudden cardiac death had no prior symptoms, making their first cardiac event fatal¹⁰.

Asymptomatic or ‘silent’ CAD is more common especially in:

- Older individuals

- People with diabetes

- Women (who are likely to present with atypical or non-specific symptoms) and especially those experiencing early menopause (before age 45)⁵

- Patients with several cardiovascular risk factors

And in 90% of these cases, doctors did not diagnose it until after death¹⁷. This asymptomatic character is important in healthcare. By the time symptoms appear or a stress test is done, coronary narrowing can be severe. This limits the effectiveness of preventive therapy⁶ and highlights the urgent, unmet need for earlier and easier coronary disease detection for patients at risk.

Causes and Risk Factors of CAD

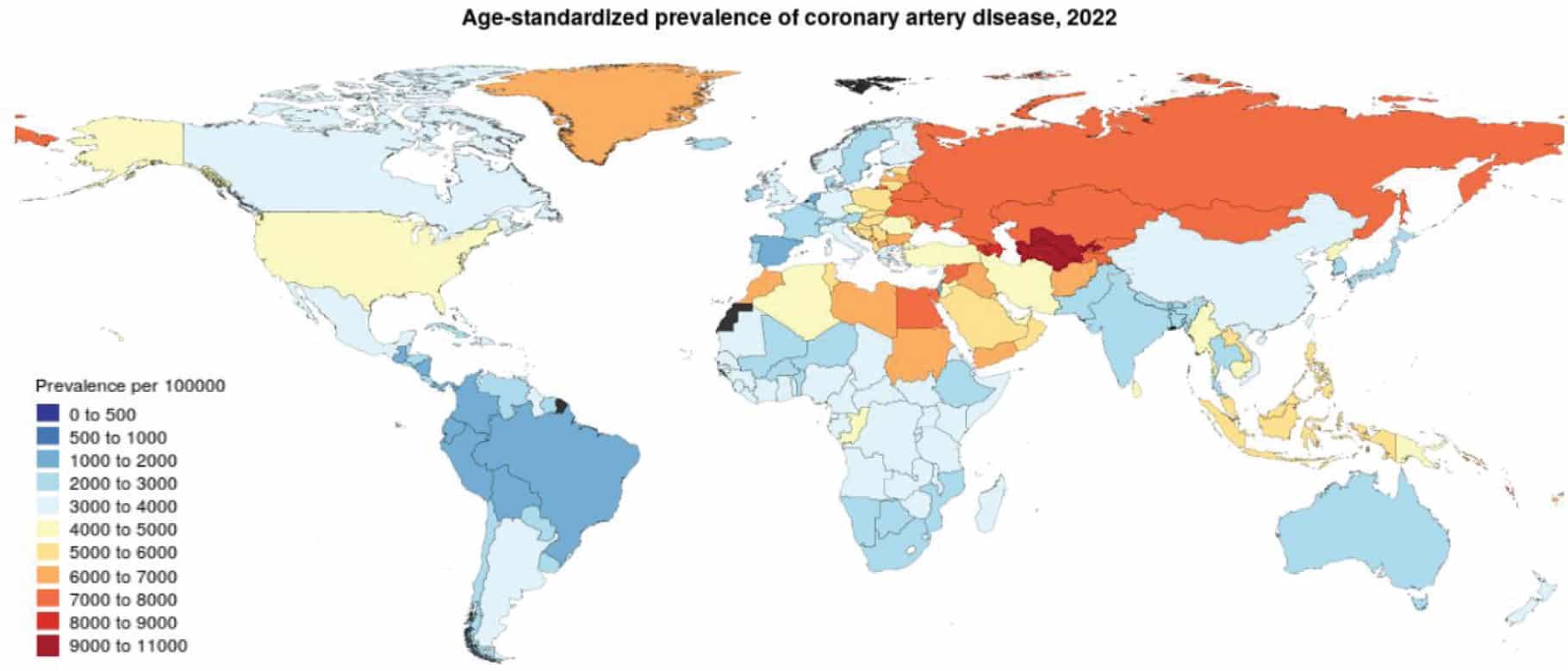

Coronary artery disease gets worse as people age. It is affected by both changeable and unchangeable risk factors for men and women.

Changeable risk factors: | Unchangeable risk factors: |

|---|---|

• High blood pressure • Elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol • Diabetes mellitus • Smoking • Obesity • Physical inactivity • Unhealthy diet | • Age • Sex (higher prevalence in men) • Family history of early CAD |

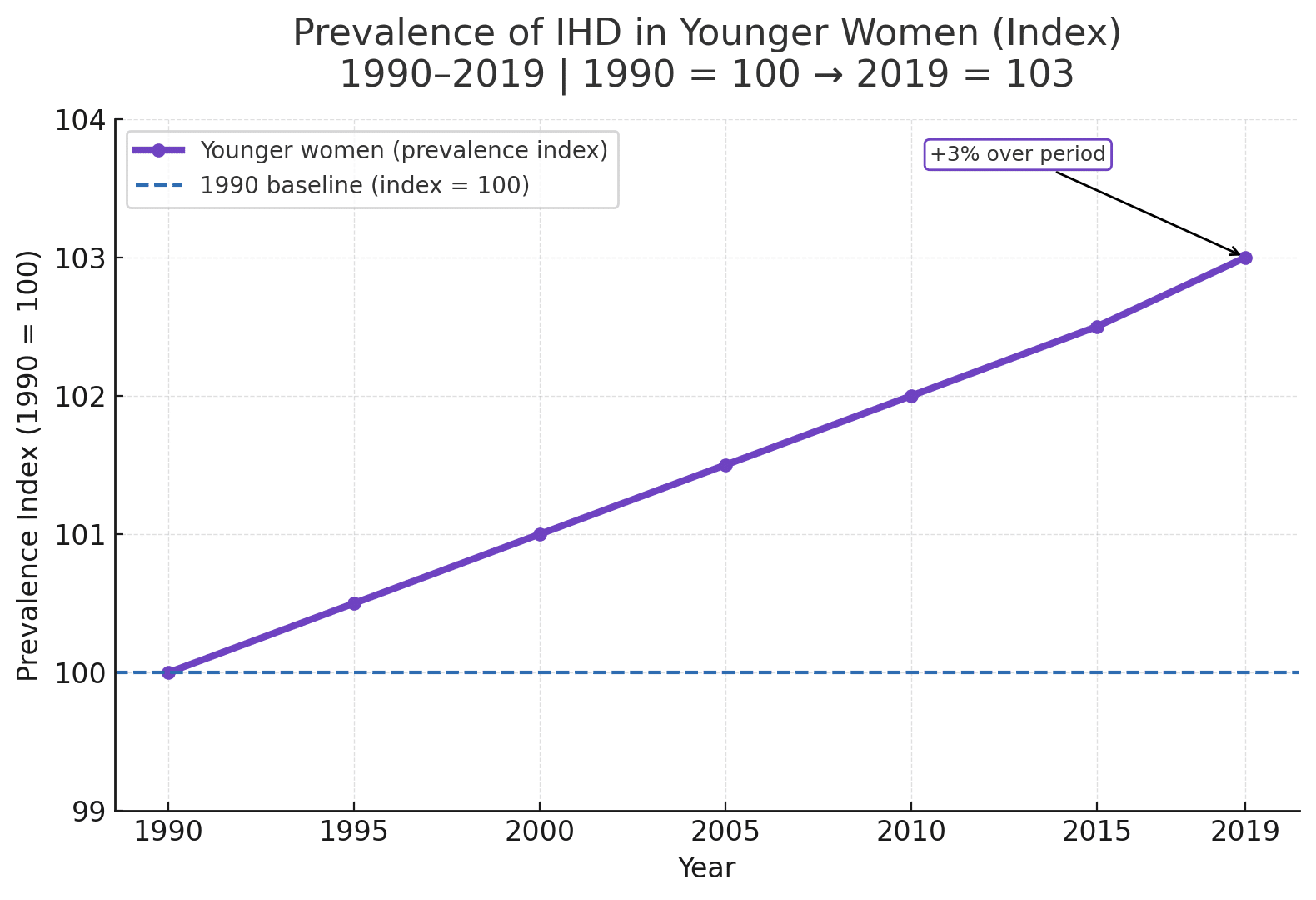

Stable Angina and Coronary Artery Disease in Younger Women

While coronary artery disease (CAD) is often perceived as a condition affecting older men, recent research highlights an important trend: ischaemic heart disease (IHD) is rising among younger women.

Between 1990 and 2019, the prevalence of IHD increased by approximately 3% in younger women, despite overall declines in global IHD mortality. Alarmingly, in some high-income countries, mortality from IHD in younger women is increasing, a trend not seen in their male counterparts¹³.

For many of these women, angina is the first sign of possible coronary artery disease. Even when considered “stable,” angina in younger women is associated with a higher risk of future premature cardiac events¹³.

Why it matters

Angina in young women may sometimes follow cyclical patterns, influenced by hormonal changes across the menstrual cycle. In addition, ovarian hormones and vascular reactivity appear to play a role in how ischemia develops and presents clinically in this group.

Although traditional CAD risk factors, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, obesity, and smoking, are shared between men and women, research shows that they can affect women differently. For example:

- Blood pressure rises earlier in life in women (as early as age 30–40) and tends to increase more rapidly than in men¹³.

- Women more frequently develop left ventricular hypertrophy and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) as a consequence of long-standing hypertension¹³.

Adherence to antihypertensive treatment can be lower in younger women, amplifying risk over time. Hormonal and reproductive factors, including pregnancy complications and menopause, can influence vascular health across the lifespan¹³.

The importance of early detection

These findings emphasize the need for proactive cardiovascular risk assessment and prevention in younger women, especially those with multiple CAD-associated risk factors. Early identification of mechanical or functional cardiac changes, before symptoms become severe, can make a significant difference in long-term outcomes.

Why Improved CAD Awareness Counts

Coronary artery disease (CAD) does not always announce itself with clear symptoms, and when symptoms do occur, they can be misleading or attributed to other conditions. This diagnostic uncertainty makes early detection challenging. In fact, a large-scale study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that over 60% of patients referred for elective coronary angiography did not have obstructive CAD, despite being referred based on symptoms or noninvasive testing⁹. This points to major weak spots in current screening methods.

Diagnostic tools like stress ECG, echocardiography, coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring, and CT angiography (CTA) are generally not recommended for routine use in asymptomatic populations. These tests are resource-intensive, costly, and require specialist interpretation, often with limited predictive value in individuals at low cardiovascular risk. While CAC scoring may be considered in select asymptomatic individuals with intermediate or borderline cardiovascular risk, its use remains context-dependent and does not change the fact that such testing is rarely justified in low-risk populations ²˒¹¹˒¹².

As a result, many people at risk remain unscreened. They face silent disease progression and sudden cardiac death. Recognizing how coronary artery disease (CAD) silently develops is key to improving early detection. Identifying the condition sooner and more accurately can prevent irreversible damage.

Rethinking Conventional CAD Testing

References

- American Heart Association. Coronary artery disease. Dallas (TX): American Heart Association; [cited 2025 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/consumer-healthcare/what-is-cardiovascular-disease/coronary-artery-disease

- Cleveland Clinic. Silent heart attack: symptoms & treatment [Internet]. Cleveland (OH): Cleveland Clinic; c2022 [cited 2025 Jun 5]. Available from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21630-silent-heart-attack

- AAPC. ICD-10-CM code I25.1 – Atherosclerotic heart disease of native coronary artery [Internet]. Salt Lake City: AAPC; [cited 2025 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.aapc.com/codes/icd-10-codes/I25.1

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. ICD-10-CM clinical concepts for cardiology [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; [cited 2025 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/medicare/coding/icd10/downloads/icd10clinicalconceptscardiology1.pdf

- British Heart Foundation. Menopause and heart disease [Internet]. London: British Heart Foundation; [cited 2025 Jul 12]. Available from: https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/support/women-with-a-heart-condition/menopause-and-heart-disease

- Kearney K. A ‘black box’: Asymptomatic stable ischemic CAD treated with PCI [Internet]. TCTMD; 2024 Apr 8 [cited 2025 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.tctmd.com/news/black-box-asymptomatic-stable-ischemic-cad-treated-pci

- Zaid G, Yehudai D, Rosenschein U, Zeina AR. Coronary artery disease in an asymptomatic population undergoing a multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) coronary angiography. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2010 Jan 29;4:7–13. doi:10.2174/1874192401004010007

- Wikipedia contributors. Coronary artery disease [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; 2024 Mar 28 [cited 2025 Aug 14]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coronary_artery_disease

- https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa0907272

- Society of Nuclear Medicine. Many die of heart attacks without prior history or symptoms. ScienceDaily. 2008 Jun 16 [cited 2025 Aug 14]; Available from: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/06/080616124938.htm

- Matta M, Harb SC, Cremer P, Hachamovitch R, Ayoub C. Stress testing and noninvasive coronary imaging: What’s the best test for my patient? Cleve Clin J Med. 2021;88(9):502–515. Available from: https://www.ccjm.org/content/88/9/502

- Eisenberg MJ. Accuracy and predictive values in clinical decision-making. Cleve Clin J Med. 1995;62(5):311–316. Available from: https://www.ccjm.org/content/ccjom/62/5/311.full.pdf

- Webb CM, Collins P. Stable angina in young women. Eur Heart J. 2025 [Epub ahead of print, 4 Feb 2025; accepted 21 Aug 2025]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/advance-article/doi/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf728/8276836

- Sinha A, Dutta U, Rahman H, Demir O, De Silva K, Morgan H, Li Kam Wa M, Ogden M, Belford S, Ellis H. Rethinking the false positive exercise stress test in the context of coronary microvascular dysfunction. Eur Heart J. 2023 Nov;44(Suppl 2):ehad655.1256. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad655.1256

- Philips Healthcare. Six technology factors that will address your challenges in delivering care to CAD patients. Philips.com. Available from: https://www.philips.com/c-dam/b2bhc/master/Specialties/cardiology/cad/eversana-editorial/six-technology-factors-to-solve-cad-care-challenges.pdf