The Limitations of Current CAD Tests

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain the leading cause of death globally, with recent estimates showing a continued rise in the total number of fatalities. In 2023, nearly 20 million people died from CVDs. Ischemic heart disease (also known as coronary artery disease or CAD) is the world’s biggest killer, accounting for roughly 9 million deaths annually¹˒². Each day, many people experience chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness or nausea. People often see these as signs of CAD. However these symptoms of heart problems are not always indicative for CAD. In fact, most people with CAD have no signs until the condition is more serious. This makes accurate and timely diagnosis extremely challenging³.

Why CAD Often Goes Undetected

Coronary artery disease (CAD) usually involves blockages in the main coronary arteries. This leads to myocardial ischemia. Myocardial ischemia happens when the heart’s need for oxygen does not match its supply.

This ischaemia-centric model, despite being present for centuries, has shown limitations in clinical practice. By the time ischaemia is detectable, the disease is often already advanced, limiting opportunities for preventive care and making treatment more invasive and costly⁸.

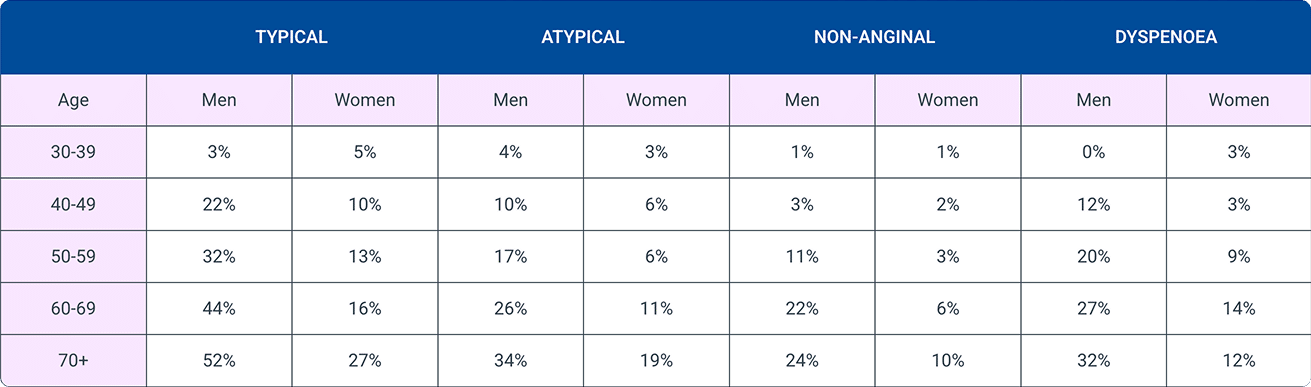

A Risk Assessment System Designed for Symptomatic Patients

Doctors calculate pre-test probability (PTP) using a person’s age, sex, and symptoms like chest pain or shortness of breath.

According to the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines, healthcare professionals should further diagnose the risk for coronary artery disease (CAD) when a person’s pre-test probability is above 15%. If PTP is between 5% and 15%, doctors may decide based on each case.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommends no testing for coronary artery disease (CAD) when a person’s pre-test probability is 5% or lower. If the PTP falls between 5% and 15%, doctors should decide on testing based on the individual case².

Patients with angina and/or dyspnoea and suspected coronary artery disease

Pre-test probability of coronary artery disease

Typical | Atypical | Non-anginal | Dyspnoea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Age | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women |

30-39 | 3% | 5% | 4% | 3% | 1% | 1% | 0% | 3% |

40-49 | 22% | 10% | 10% | 6% | 3% | 2% | 12% | 3% |

50-59 | 32% | 13% | 17% | 6% | 11% | 3% | 20% | 9% |

60-69 | 44% | 16% | 26% | 11% | 22% | 6% | 27% | 14% |

70+ | 52% | 27% | 34% | 19% | 24% | 10% | 32% | 12% |

Click to enlarge table

In practice, most screening for coronary artery disease (CAD) still centers on common symptoms, rather than a person’s actual risk factors such as underlying physiology or family history, even though all three contribute significantly to coronary risk³.

As a result, individuals who do not present symptoms but may have underlying coronary conditions are often classified as low risk. These individuals typically aren’t screened for CAD and are rarely referred for further risk assessment. This symptom-based approach means silent CAD frequently goes undetected, excluding many at-risk individuals from existing screening protocols.

The Inefficacy of Symptom-Based CAD Risk Screening

Even in patients with symptoms, available risk screening tests are less than ideal. Studies show that 4 out of 5 patients sent for testing don’t have obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD). Most tests come back negative, yet many patients still go through extra procedures and face higher costs, even though they’re not truly at risk⁴.

This over-referral leads to:

- Improper usage of limited healthcare resources

- Unnecessary patient anxiety

- High system costs

- Delays in identifying those truly at risk

Not only is CAD underdiagnosed, it is overexamined in the wrong populations.

Diagnostic Gaps Across Care Settings

The issue is not limited to general practice. Across hospitals and clinics, healthcare professionals decide who gets tested for coronary artery disease (CAD) based on a person’s symptoms. But these symptoms don’t always match the real disease, so many cases go missed or misjudged.

As a result:

- Emergency departments often overuse high-cost imaging⁵

- General practitioners often refer patients to rule out CAD when faced with diagnostic uncertainty⁶

- Specialists face overloaded workflows when evaluating false positives⁷

Current screening technology is reactive, designed to confirm disease after symptoms appear. But the opportunity is truly in identifying CAD risk sooner, especially in high risk patients with multiple CAD-associated risk factors. Not only will it improve clinical outcomes, but it will also significantly reduce the healthcare burden.

Explore Partnerships

Looking to improve patient outcomes and reduce unnecessary testing with a scalable, cost-effective, and patient-friendly CAD screening solution?

References

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; [cited 2025 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases#tab=tab_1

- World Health Organization. Global Health Estimates: Leading causes of death [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; [cited 2025 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death

- Alizadehsani R, Abdar M, Roshanzamir M, Khosravi A, Kebriaei H, Khozeimeh F, et al. Clinical updates in coronary artery disease: A comprehensive review. J Clin Med. 2024;13(16):4600. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/13/16/4600

- Koloi A, Loukas VS, Hourican C, Sakellarios AI, Quax R, Mishra PP, Lehtimäki T, Raitakari OT, Papaloukas C, Bosch JA. Predicting early-stage coronary artery disease using machine learning and routine clinical biomarkers improved by augmented virtual data. Eur Heart J Digit Health. 2024 Sep;5(5):542–550. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjdh/ztae049

- Al-Sabah A. Understanding early detection of coronary artery disease. J Coron Heart Dis. 2024;8(5). Available from: https://www.hilarispublisher.com/open-access/understanding-early-detection-of-coronary-artery-disease.pdf

- Lanza GA. The role of ECG exercise stress testing in the assessment of patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Eur Cardiol Rev. 2025;20:e16. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12159857/

- Vandeloo B, Andreini D, Brouwers S, Mizukami T, Monizzi G, Lochy S, Mileva N, Argacha JF, De Boulle M, Muyldermans P, et al. Diagnostic performance of exercise stress tests for detection of epicardial and microvascular coronary artery disease: the UZ Clear study. EuroIntervention. 2023;19:e1090–e1099. Available from: https://eurointervention.pcronline.com/doi/10.4244/EIJ-D-22-00270

- Gibson CM, Boden WE, Theroux P, Col J, Hamm CW, Gupta M, et al. The use of the exercise treadmill test in the era of coronary risk stratification: time to revisit its role? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(9):1450–5. Available from: https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02897-8

- Skjelbred T, Warming PE, Krøll J, Andersen MP, Torp-Pedersen C, Winkel BG, et al. Sudden cardiac death as first manifestation of cardiovascular disease: a nationwide study of 54,028 deaths. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2025 May;11(5):881–90. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39918459/

- Corrado D, Thiene G, Pennelli N. Sudden death as the first manifestation of coronary artery disease in young people (≤35 years). Eur Heart J. 1988 Dec;9 Suppl N:139–44. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3246245/

- Vähätalo J, Holmström L, Pakanen L, Kaikkonen K, Perkiömäki J, Huikuri H, et al. Coronary artery disease as the cause of sudden cardiac death among victims <50 years of age. Am J Cardiol. 2021 May 15;147:33–8. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002914921001570

- Hecht HS, Cronin P, Blaha MJ, et al. 2016 SCCT/AHA/ACC/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCAI/SCMR Expert Consensus Document on Coronary CT Angiography in Normal Risk Individuals (Class III Recommendation). Circulation. 2016;134(10):e153–96. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCORDERS.0000000000000420

- Wikipedia contributors. Cardiac stress test [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; 2024 May 31 [cited 2025 Jun 5]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cardiac_stress_test

- Michalowicz BS, Xu J, Patil KD, Sandoval Y, Fordyce CB, Newby DE, et al. All models are right but some are more useful: comparison of pre-test probability models for coronary artery disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12(4):e027260. doi:10.1161/JAHA.122.027260. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9798801

- Douglas PS, Nanna MG, Kelsey MD, et al. Comparison of an initial risk-based testing strategy vs usual testing in stable symptomatic patients with suspected coronary artery disease: the PRECISE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2023 Aug 23 Available at: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamacardiology/fullarticle/2808765

- Therming C, Galatius S, Heitmann M, Højberg S, Sørum C, Bech J, et al. Low diagnostic yield of non-invasive testing in patients with suspected coronary artery disease: results from a large unselected hospital-based sample. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2018;4(4):301–308. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29267950/

- Hoffmann U, Truong QA, Schoenfeld DA, et al. Coronary CT angiography versus standard evaluation in acute chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(4):299–308. Coronary CT Angiography versus Standard Evaluation in Acute Chest Pain | New England Journal of Medicine

- Winkler K, Gerlach N, Donner-Banzhoff N, et al. Determinants of referral for suspected coronary artery disease: a qualitative study based on decision thresholds. BMC Prim Care. 2023;24:110. Available from: https://bmcfampract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-023-02064-y

- Okamura T, Novak J, Kimura Y, et al. Challenges and burdens in the coronary artery disease care pathway. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(10):6352. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10177939/